Training For Mind-Body Resilience

Wednesday, April 3, 2013 at 11:55PM

Wednesday, April 3, 2013 at 11:55PM by Kelly McGonigal, PhD for IDEA Journal

*The full article is not represented here*

Research explores how exercise can protect against the harmful effects of chronic stress.

Think of a recent time you felt stressed. Maybe it was during an argument with your spouse, or a meltdown with your kids. Maybe you were stuck in traffic and late for an important meeting. Or maybe you were lying in bed, worrying about work. Whatever the cause of your stress, your body and brain were almost certainly experiencing the same thing: boiling blood pressure, a churning stomach, tight muscles and a racing mind.

We all recognize this feeling of stress. It’s more than a mental state; it’s a full-blown mind-body response. When stress takes hold, the brain is bathed in chemicals that heighten our senses and focus our attention, making it impossible for us to think about anything else. The sympathetic nervous system gets a jump-start, and stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol make us feel even more wired. Glucose and fats flood the bloodstream, and our cardiovascular and respiratory systems rev up, all to give us the energy we need to deal with the stress.

These changes would make sense if we were running for our lives or rescuing our child from a fire. But when everything from taxes to television news triggers a reactive response, stress becomes toxic. Chronic stress increases the risk for a wide range of health problems, in large part because the body’s response to stress adds up over time (McEwen 2006). Chronic inflammation and sympathetic activation contribute to autoimmune disorders, chronic pain and cardiovascular disease. Elevated blood glucose and fat levels raise the risk of insulin resistance and diabetes. Chronic exposure to stress hormones suppresses the immune system, kills off brain cells and promotes obesity. When any unwanted physical or psychological condition is present, chances are that stress plays a role.

And yet, not everyone is equally susceptible. Some people seem to be protected from the worst effects of stress. These resilient folks handle stress better and recover from stress more quickly. Science is beginning to reveal the secrets of stress resilience and to learn what it looks like in the brain and body. It turns out we can measure stress resilience in the heart, the nervous system (which includes the brain) and even our DNA. We can also train resilience—even in the face of chronic stress.

This article explores the new biology of stress resilience, how it protects against stress-related diseases, and why exercise may be the best way to train it.

Our Resilient Heart

For many, the heart is where we first feel stress. We sense it speeding up or pounding in our chests. The heart is also where researchers discovered the body’s best biological indicator of stress resilience:heart rate variability.

Although we typically describe heart rate with one number (e.g., 70 beats per minute), heart rate naturally fluctuates from moment to moment; in other words, across those 70 heartbeats, the time between beats varies slightly. When the autonomic nervous system is balanced between sympathetic and parasympathetic activation, HRV coordinates with the breath. The time between heartbeats gets shorter when we inhale and longer when we exhale. This kind of HRV is not only normal; it’s a sign of cardiovascular health (Thayer et al. 2011; Thayer, Yamamoto & Brosschot 2010). It means the body is not stuck in a chronic fight-or-flight response. For this reason, HRV is sometimes referred to as autonomic resilience.

Researchers have discovered that people with greater resting HRV respond better to stress than people with lower HRV (Thayer et al. 2011). The former cope better with mental, emotional and social stress; adapt more quickly to stressful environments; and recover more quickly from stressful experiences (Souza et al. 2007). HRV appears to be a kind of “resilience reserve” that buffers against the physiological and psychological toll of stressful experiences. Psychological disorders defined by their loss of stress resilience—including depression and posttraumatic stress disorder—are associated with chronically lower HRV (Dedert et al. 2010; Stapelberg et al. 2012).

Does Exercise Increase HRV?

A growing body of research demonstrates that regular physical activity can increase resting HRV. For example, a recent study examined the effects on HRV of 12 weeks of intermittent aerobic exercise (20 minutes, 3 times per week) in a group of previously sedentary young men (mean age = 24.9 ± 4.3 years) with an average body mass index of 28.7 ± 3.1 (Heydari, Boutcher & Boutcher 2012). The workout consisted of indoor cycling at 80%–90% of maximum heart rate interspersed with recovery periods. Men in the exercise group showed an increase in baseline/resting HRV, while men in the control group showed no change.

Obesity is commonly associated with lower HRV (de Souza et al. 2012), but research indicates that exercise can increase HRV in obese individuals. Overweight and obese middle-aged men and women who participated in a 12-week aerobic cycling program (30 minutes, 3 times per week) experienced an increase in HRV (Amano et al. 2001). In another study, obese women who had recently undergone gastric bypass surgery showed an increase in HRV after 12 weeks of aerobic treadmill exercise (1 hour, 3 times per week) (Castello et al. 2011).

Medical researchers have begun to view HRV training as a key goal in treating stress-related disorders such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and exercise as a proven method for doing so. A 2010 review paper (Routledge et al. 2010) identified 18 studies demonstrating that exercise increases HRV among people with stress-related disorders. The exercise interventions in these studies varied widely, ranging in length from 4 weeks to 6 months, with workouts as diverse as unsupervised walking and carefully structured indoor cycling. The one common feature of all programs was that they involved some form of cardiovascular exercise.

How Much Exercise Is Enough?

A study of overweight and obese postmenopausal women found that moderate exercise was sufficient to improve HRV (Earnest et al. 2008). The subjects—373 previously sedentary women, aged 45–75—were randomly assigned to 6 months of exercise training at 50%, 100% or 150% of the minimal physical activity levels recommended by the National Institutes of Health. Exercise improved HRV, but the dose-response relationship was nonlinear. Exercising at the 50% level did not increase HRV; benefits occurred at the 100% level; but the most active group gained no additional benefits.

A correlational study of adolescents found a similar association between moderate physical activity and higher HRV (Radkte et al. 2012). The teens in this study wore an accelerometer for 8 days and an HRV monitor for one 24-hour period. Those who engaged in more frequent physical activity had higher 24-hour HRV than less active students. But this finding held true only for moderate physical activity; greater high-intensity activity did not correlate with higher HRV.

Together, these results suggest that resilience training can begin with modest increases in activity. In the teen study (Radkte et al. 2012), only 17 minutes of daily activity separated those with high HRV from those with low HRV.

Our Resilient DNA

Scientists have recently discovered that stress resilience (like stress itself) goes much deeper than the signs of stress we easily feel or see. It goes all the way down to our DNA, the genetic material—present in every cell—that holds the so-called blueprint for life. The latest research suggests that stress can damage DNA and increase our risk of age-related diseases like cancer, cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease (Aubert & Lansdorp, 2008; Willeit et al. 2010). Fortunately, exercise can protect our DNA, slow down the body’s aging process and reduce the risk of age-related diseases.

Telomeres: The Guardians of Your DNA

You may remember from biology class that the body’s cells replicate themselves throughout our lifespan. Each time a cell replicates, it loses a bit of its DNA. To make sure that cells don’t lose important DNA, the ends of chromosomes are padded with extra sequences of spare DNA. These protective ends are called telomeres. The spare DNA can be sacrificed without damaging the cells’ ability to replicate. In this way, telomeres preserve the integrity of our DNA (Aubert & Lansdorp, 2008; Willeit et al. 2010).

However, as we age and cells repeatedly turn over, our telomeres get shorter. This can lead to cell death and dysfunction. Telomere length has become a cutting-edge biological measure of a person’s true biological age (Fyhrquist & Saijonmaa 2012). Telomere length is associated with remaining lifespan, as well as a wide range of age-related diseases, from cancer to cognitive decline (Ludlow & Roth 2011; Yaffe et al. 2011).

Scientists have discovered that time is not the only thing that shortens telomeres. Psychological stress speeds up the rate of telomere shortening and slows down the body’s process for repairing telomeres (Blackburn & Epel 2012). In fact, much of what we think of as age-related decline may actually be due to the effects of stress on telomeres. But this effect is not inevitable. New research reveals that telomere shortening can be prevented—and even reversed—through stress reduction and healthy lifestyle changes (Epel 2012).

While anything that reduces stress can have a positive effect, physical exercise may have a particularly potent impact on telomere length. One study analyzed the relationship between physical activity and telomere length in 2,401 adults (mostly women, with an average age of 48.8 ± 12.9). Regular exercisers had longer telomeres than nonexercisers, and the average difference in length was equivalent to 10 years of biological age (Cherkas et al. 2008). Another study found that greater cardiovascular fitness, as measured by a treadmill test, was associated with longer telomeres (Krauss et al. 2011).

Exercise even seems to erase the usual association between higher levels of psychological stress and shorter telomeres. In one study, sedentary postmenopausal women who reported greater stress had significantly shorter telomeres. However, among women who met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendations for physical activity, there was no correlation between stress and telomere length (Puterman et al. 2010).

Moderation Wins Again

As we saw for heart rate variability, the benefits of exercise on telomere length appear to be strongest with moderate levels of exercise. Among middle-aged and older adults, physical activity is associated with longer telomeres, but only up to an average expenditure of 2,341–3,540 kilocalories per week (which equates to about 10 hours of walking or other light activity per week). One study found that adults reporting higher levels of activity had telomere lengths equivalent to the least active participants (Ludlow et al. 2008).

Another study tracked 204 middle-aged men from 1974 to 2003 and used 1974 activity levels to predict telomere length in 2003. Researchers grouped the men into three categories: light activity (mainly reading, watching television or movies, and other sedentary activities), moderate activity (e.g., walking, cycling, skiing, gardening or other light exercise at least once a week) and vigorous activity (e.g., running, vigorous exercise or competitive sports several times a week). Moderate, but not vigorous, activity in midlife predicted longer telomeres in old age, compared with the light-activity group (Savela et al. 2013). These findings suggest, again, that crossing the line from sedentary to active is the most reliable way to increase stress resilience.

The Resilient Brain

Psychological stress begins in the brain when we perceive a threat. The brain triggers the body’s fight-or-flight stress response and directs the process of stress recovery. It should be no surprise, then, that the search for the biology of stress resilience must include the brain.

How Stress Shapes the Brain’s Stress Circuit

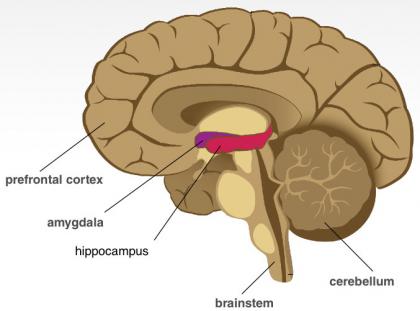

Three regions of the brain control the stress response: theamygdala, which detects threat and triggers the fight-or-flight response; the prefrontal cortex, which helps us deal calmly with stress, and can prevent or shut down a fight-or-flight response; and the hippocampus, which supports stress recovery (McEwen & Gianaros 2010).

Neuroscientists now know that chronic stress can change these brain regions in a way that makes us more sensitive and less resilient to stress (Ganzel, Morris & Wethington 2010; McEwen & Gianaros 2010). For example, high levels of stress hormones are neurotoxic to the prefrontal cortex or hippocampus, can reduce the connections between brain cells and can even kill brain cells. As these areas weaken, the brain gets worse at managing stress. Chronic stress has the opposite effect on the amygdala, the brain’s threat detector. Repeated stress can actually make the amygdala grow, increasing connections between brain cells and heightening cell excitability. This makes the brain even more reactive to stress. These brain changes are associated with, and likely contribute to, a range of stress-related disorders, from depression to cardiovascular disease and accelerated aging (Ganzel, Morris, & Wethington 2010).

How Exercise Changes the Brain

Exercise has shown tremendous promise as a neuroprotective intervention (Fleshner et al. 2011; Head, Singh & Bugg, 2012; McEwen 2012). Research has identified several ways that exercise protects the brain from stress—and even reverses the effects of chronic stress on the brain (Stranahan & Mattson 2012; Rothman & Mattson 2012). Exercise increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which maintains brain health, supports brain growth and combats the negative effects of stress. Exercise seems to enhance BDNF specifically in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, the two regions most susceptible to stress-related damage. Exercise also triggers the brain’s self-repair processes, which may help reverse any stress-related neurotoxicity. Finally, exercise activates the brain’s stress-calming system, releasing a neurotransmitter called GABA, which helps restore balance in the autonomic nervous system. When we exercise regularly, we naturally engage all of these neuroprotective processes. Over time, exercise can create a “stress-resistant” brain that is less sensitive to threat and recovers more quickly from stress (Fleshner et al. 2011).

.....

What Else Trains Resilience?

Although exercise holds great promise as a resilience booster, research also points to other interventions that may train resilience.

Meditation and mindfulness training. Meditation training has been shown to protect and lengthen telomeres (Jacobs et al. 2011; Lavretsky et al. 2013), as well as increase autonomic balance and heart rate variability (Tang et al. 2009.; Wu & Lo 2008). Mindfulness meditation training has likewise been shown to create changes in brain structure associated with greater stress resilience, including increased volume and density of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, and decreased volume of the amygdala (Hölzel et al. 2011).Fasting or calorie restriction. Animal research has demonstrated that intermittent fasting and overall calorie restriction increase longevity by acting as a good stressor on the brain and body. Human research is less conclusive, and these strategies can be difficult to sustain in a healthy way. Nevertheless, some scientists recommend intermittent fasting (e.g., 12 hours every day without food) or calorie restriction as a potential intervention to increase stress resilience and prevent age-related diseases (Rothman & Mattson 2012; Stranahan & Mattson 2012).A less-processed, plant-based diet. A more sustainable alternative to fasting is resilience-promoting nutrition. Eating a less processed and more plant-based diet has been associated with both higher heart rate variability and longer telomeres (Fu et al. 2008; Mirabello et al. 2009; Lin, Epel, & Blackburn 2012). This type of diet likely increases resilience by reducing inflammation, insulin resistance and other metabolic risk factors associated with chronic stress. Some scientists also believe that specific micronutrients and phytochemicals in this kind of diet selectively trigger positive stress adaptation in the brain (Stranahan & Mattson 2012).

Reader Comments